“21st Century Dry Film Polymer (Direct-to-Plate) Photogravure” The photogravure at last made far more easily, and very, VERY much less expensively!

Click on “Go To Web Site” above, then click on “Books..”

During the 1980’s and early 90’s when I was more inclined to be inventive, one of the many ideas I had that never saw print was to use color film for making B&W photographs. Unfortunately, not all the pieces were in place at the time. They did all come along, sort of, eventually, but not in an order that was conducive to the actual birth of such an approach. Not until now, anyway.

You see, much of making a fine art B&W photograph has to do with the manipulation of color. I have talked about this before on this blog. One can manipulate gray tones by manipulating the colors of a scene and by choosing the color sensitivity of one’s B&W film. Choices are limited now, but once, you could choose between films sensitive to only blue light, or blue and green, or blue green and red; today’s modern panchromatic films. There are still blue and blue/green sensitive films, but for the most part they are special purpose films, usually of higher contrast than normal.

The colors in the scene were manipulated by the choice of color filter through which the photograph was taken. Filters lightened their own colors and darkened all the others. Between filters and film choice, the alteration of gray tones was a useful tool, but not broadly so. You could only use a single filter per photograph. If more manipulation was wanted, tough!

Some years ago I invented and published a technique called Dye Dodging. It involved using specialized dyes employed by color photograph retouchers. I repurposed them to manipulate the gray tones of a B&W image, in the darkroom. A blank piece of film was attached to the top of the negative and both made immobile in the negative carrier of an enlarger, so that the carrier could be removed from the enlarger, the dyes applied to the blank sheet of film where required and the carrier returned to the enlarger for a fresh print. The blank sheet threw the dyes out of focus so that the work done was not detectable in a print. It was quite effective. Sadly, this technique is no longer available because the dyes no longer exist. The lady who manufactured them and taught their use is deceased. (This did not stop an entirely shameless individual from publishing what he mis-represented as his own idea, an idea blatantly borrowed from the early 20th Century and having nothing whatsoever to do with my technique, under the title: Dye Dodging. And he did so in the exact same magazine where I had published the original Dye Dodging technique. Unfortunately, the magazine had a new editor who was something less than observant.)

At any rate, if memory serves me, the concept of dye dodging was what stimulated my original thinking on the subject of using color negative film for capturing B&W photographs: the logic being that if images were captured on color film, there would be no need for the tedium of using color filters or choosing which film might be more appropriate at the moment. A standardized approach could be taken to image capture and color manipulation of gray tones could be postponed until later, in the darkroom. This would also allow experimentation with different gray tone alterations based on color. The scene colors would be there in the negative, so all the filters could be available via a single image capture. This broadened the potential printing options for a B&W image, considerably.

A great idea that was fundamentally sound, except for a few deal breakers. There was no Zone System for color negative film. That would come later, but I could not know in advance what I, or others might invent. (Working separately, I and a fellow named Robert Anderson, invented complete contrast control for both color negative film and color paper, unknowingly announcing our discoveries in the same issue of the same magazine, in 1990.) So, there was no contrast control via film development for color negative film, at the time. Development of color negative film was standardized. And there was no paper on which to make B&W images from color negatives: well, not a viable one.

There was a paper for just this purpose. Kodak made it and it was called Panalure. It was a panchromatic B&W paper designed specifically for making B&W prints from color negatives. But it came in only one contrast grade (again, this problem was at least partially remedied by later inventions, but I could not know it at the time). No approach to B&W fine art photography could be based on a single grade of paper, but worse, far worse…

Panalure was a resin-coated paper: anathema to the fine art B&W photographer. No self-respecting artist would ever consider offering prints made on a plastic paper. That was the end of the trail.

So there you have it. The lack of an adequate paper for printing was the real killer of this idea. Until now!

Digital photography, in particular the scanner and the inkjet printer, have breathed, if not new life, at least new viability, into this concept. Now, a photographer can capture an intended B&W photograph on color negative film, scan the negative and alter gray tones via the manipulation of the colors, in Photoshop. Whether printed digitally or a new negative made for printing by chemical means, this route is finally viable.

Of course, one can now accomplish very much the same thing with a high-end digital camera, so the desire to stick with film must be strong. And then there is the fact that only three color negative films still exist in sheet film sizes, all made by Kodak and carrying, shall we say, impressive prices. Though I think B&W films will be around for a very long time yet, I suspect color negative films will soon breath their last. All the indicators point in that direction. After all, Kodak makes color films for which they DO NOT make a single paper on which to print them!

The approach now actually exists, though somehow I doubt it will be a blockbuster. Timing IS everything!!

dk

I have no idea why I would have thought the advent of digital photography might reduce the stupidity that haunts the photographic world. The disappearance of all those photography magazines that specialized in selling snake oil to hobbyists made me think the nonsense might be over. Not a chance. It persists and even thrives.

If you have children, you have no doubt played “Whack-a-Mole”: that silly game found at chain restaurants serving bad pizza and paper bowls of sticky macaroni and cheese; restaurants designed to appeal to both children and parents fond of explosive diarrhea. Writing about photography is a constant game of “Whack-a-Mole”. The very same stupid and indestructible ideas keep popping up over and over, no matter how many times someone tries to exterminate them. Some of these recurring stupidities span CENTURIES. Three centuries, in this particular case.

In the 1800s, photographers knew little if anything about how photography worked or how to control it. Hurter and Driffield would not come along for a while yet and photographic processing was more like alchemy than anything else. Photographers put things into their developers that provided no benefit whatsoever, or worse, diminished the outcome of the development process considerably. One of the really bad ideas of the era was to suspend your film in developer, walk away and come back an hour or two later. This was called stand development at the time, among other names, and achieved considerable popularity, as incredibly stupid ideas generally do. It was born of ignorance and superstition, and produced considerably less than optimal results. Little or no agitation was provided so, uneven development combined with severe over-development was usually the result.

Later, this kind of development approach was modified to be employed as a method of contrast reduction in order to accommodate negatives exposed to a too-long range of subject reflectances. There were several variations on this theme for contrast reduction and they worked moderately well because agitation was reduced, not eliminated, developer dilution was generally increased, and time and temperature were carefully controlled instead of left to chance, as with the original concept of stand development. Instead of leaving film in the developer for hours, it was removed before heavily exposed areas had a chance to approach full development. A very bad idea was converted into a fairly good one.

In the early 1990’s I wrote a four part series of articles on the topic of contraction, a more modern term used to describe the intentional modification of film development in order to reduce negative contrast: the various old, but useful, contrast reduction techniques that morphed out of the original bad idea of stand development.

The first in that series of articles explained in considerable depth and with more than ample proof, why those older contrast reduction techniques were lacking, had all along been used to address the wrong problem and had become even less efficient in their action because of recent improvements in film technology that reduced their original, limited effectiveness.

I don’t know who the 19th century assassins of stand development might have been. Possibly Hurter and Driffield, themselves. It was nonetheless, well murdered somewhere between the late 1800s and the next century. Photographers stopped repeating that nonsense completely: for, oh, say, a century or so.

In the mean time, I did my very best to kill the offspring of stand development in that 1990s series of articles and even offered up some sound and versatile replacement techniques in the same series. It seems my skills as an assassin are not quite adequate. The old obsolete techniques are still used widely. Oh well, I understand that bloodletting is also making a comeback.

But more astonishing than the continued survival of antiquated contrast reduction techniques, and bloodletting, is the recent return of stand processing. I am still aghast at finding proud declarations on the internet almost every day that film X was stand developed or, semi-stand developed (meaning the photographer had the good sense to employ at least some agitation). At least there are no patients proudly proclaiming their doctors applied leeches! (Or, are there?)

Dredging up an old, failed development approach is bad enough, but the excuses for doing so are worse. Far worse. A number of proponents of the newly rediscovered stand development approach actually have the gall to claim that, normal development with agitation, and while paying attention to time and temperature, is just too difficult and tedious for them. They simply don’t have the time to stand there for five or ten minutes paying attention to one of the most simple and straightforward chemical processes on Earth. (Seasoning food is often significantly more difficult!) It makes one wonder if they also have difficulty brushing their teeth or washing behind their ears.

Others claim they get sharper images with stand development. Some make this claim while in the same breath, lamenting that their negatives are often unevenly developed! Well, DUH! Stand development is a written guarantee for uneven development. Uneven development was in large part responsible for the original demise of stand development.

In their defense, users of stand development may in fact, sometimes get what appear to be sharper images. They are not sharper, but they can appear to be. Sometimes. Higher accutance, which is a result of what is called the adjacency effect in film development, is the source of this illusion of increased sharpness. It is a genuine effect, though slight. There are developers and approaches to development that do indeed produce the illusion of greater sharpness. They were useful when lenses and films were considerably less sophisticated than they are today. There is now little need for accutance developers. Films have advanced a great deal. So have lenses.

One cannot criticize a photographer who proclaims a need for sharper looking images, a possibly legitimate pursuit… unless of course, that photographer happens to be one whose images are not sharp because he does not use a TRIPOD: the usual reason for unsharp images. What is the point of claiming a desire for sharper images when the photographer insists on doing the very thing required to guarantee unsharp images? Many of the images I see on the internet, the makers of which proudly proclaim their use of stand development, are quite clearly images captured without the benefit of a tripod. Actual image sharpness is a product of a good lens and A TRIPOD!!! Not of magic development. No approach to film development can remotely match the increased real sharpness provided by a tripod. If you do not use a tripod, do not dare claim you use a developer because you want increased sharpness!

About the most ridiculous excuse I have seen thus far is, “I need those ten minutes for more important pursuits.” You know what, I refuse to dignify that by even commenting on it.

At this point, the only thing I wonder about is whether or not this moronic idea will actually make it to the next. a fourth century! I’m betting that it will. Any takers?

I was going to quit writing right here and save my next thought for tomorrow. But two curmudgeonly posts are not better than one, so I will tack it on here and bring up a second stupidity, while finishing the venting of my spleen at the same time. This is a modern stupidity, one that I could not entirely fathom until just today. It is called, Bokeh, and will no doubt, also span centuries.

Bokeh is a made up term for the appearance of out-of-focus areas of a photograph. It is apparently a bastardization of a Japanese term. I started seeing comments regarding bokeh on the internet about ten years ago, like: “Oh, what beautiful bokeh your photograph has” or, “this lens has better bokeh than that lens“!

Bokeh has been adopted as yet another pointless distraction for many photographers to use as an excuse not to get about the hard work of making photographs worth seeing. That I understand. Photographers have always sought out such excuses. It explains most of the photographic gadgets on the market.

An out of focus area in a photograph is either there intentionally, or due to incompetence. If it is due to incompetence, the photographer probably would not want viewers staring into it and marveling at it.

If it is there intentionally, then clearly the photographer wished to direct the viewer’s attention elsewhere in the photograph, causing one to wonder why anyone would be remarking how beautiful the out-of-focus area may or may not, be! If they are doing so, then the photographer obviously failed in his attempt to redirect attention. The supposed beauty of such a failure, is irrelevant. If viewers are looking where the photographer clearly intended they not look, the photograph is landfill.

When I first started writing articles for photography magazines, I made the mistake of allowing a couple of my articles to be published in a widely-read, though somewhat less than credible magazine. When you offer up new technical information, where you publish it is everything, if you expect your work to be taken seriously. The results of your new medical research will be widely ignored if you publish it in German Shepherd Monthly. I regretted giving those articles over to that questionable magazine almost from day one. The magazine had no credibility.

(The majority of my articles were published in Darkroom & Creative Camera Techniques, a highly respected magazine that suffered no such lack of credibility. Fortunately, all my more important articles appeared there.)

The Brand X magazine (German Shepherd Monthly), on the other hand, had a reputation, of which I was unaware, for publishing nonsense along with the occasional more worthwhile content. Among other things, advice to wash your film in the toilet in case of water shortage, or to use dish soap in place of Photo-Flo, just in case the world ran out of Photo-Flo, are things that stick in my mind. Can’t imagine why! In fact, I have mentioned those two ideas in the past, possibly in the hope that doing so might somehow result in my absolution for that regrettable, though brief, association.

Today I learned for the first time that Bokeh burst on the scene as a contribution from the exact same person who headed that Brand X rag when the toilet and dish soap ideas were published. Now, it all finally makes sense! They are three ideas that clearly come from the same source and all belong together… filed under, useless.

So, if you should run into someone preoccupied with bokeh, tell him you want to teach him a wonderful new development process for negatives with bokeh, called, still development: in toilet water; with dish soap. And toss a teaspoon of instant coffee into the developer while you’re at it, just for good measure.

http://www.adweek.com/digital/bonnier-popular-photography-magazine/

The long-time magazine, Popular Photography announced its immediate end this week. Their web sites, too. They are done. Over. Finished. Kaput. Belly-up. Not changing to the web; gone completely. The current issue is the last issue. The last thing they put on their web site(s) is the last thing they will ever put on their web sites.

This magazine along with Modern Photography, a similar circulation size and content publication bought out by Popular Photography just a few years ago were by far the two most significant players in the world of hobby photography for nearly a century. At least eight/tenths of a century, anyway.

If an official line demarcating the end of the hobby of photography is possible, this is it. The special audience magazines I used to write for had circulations of 60-70,000 at most. These two had circulations approaching a million, each, perhaps more in their heyday.

I have mixed feelings about this. I always had significant disdain for both Pop and Modern Photography. Their very clear reason for existing was always, I felt, counterproductive. Their purpose was to lead hobbyists down the primrose path, turning them from potential photographers into collectors of idle and largely useless equipment. There was little or nothing of value to learn from these magazines. And what little information they did impart was quite often glaringly wrong. But, it was wrong information that sold more gadgets and more film, etc., etc. In hindsight, they weren’t creating the equipment collectors, just satisfying them. Most of these readers didn’t really want to put in the effort to become photographers, they wanted magic bullets that the magazines obligingly offered them. In other words, they not only wanted to be lied to, they demanded it!

But these magazines and their readers were also a great benefit to my corner of the photography world, the fine art photograph. Let’s face it. The fine art photography world is a tiny world, indeed. And, we have always done a lousy job of marketing ourselves and educating our audience. AN EXCEPTIONALLY LOUSY JOB!!!

The vast majority of the public does not have so much as a subatomic-sized clue what a fine art photograph is, or looks like. Especially in the United States! Oh, brother! Don’t think so? Your honor, I present as evidence, Peter Lik. Your honor, I rest my case.

The benefit provided to art world photography by Popular Photography and Modern, and their readers was the mass demand that drove and supported the manufacturers of photographic materials. Millions of budding hobbyist photographers wanted to emulate the likes of Ansel Adams, and of course, a slew of nature and vacation and wildlife photographers. They also wanted to emulate professional commercial, portrait and architectural photographers.

Fine art photographers and commercial photographers added together were still a very tiny market compared to the hobbyist and vacation snapshooter. Those were the people who provided the massive income that allowed manufacturers to invest in the research and development that produced the finer materials that my little corner of the world would never have had without them.

If not for us, those hobbyists would not have had anyone to try to emulate, but if not for them, we might never have had the materials we depended on, at all, or the audience we needed to gain world attention. It was an accidental, symbiotic relationship.

Now, there are no magazines promoting photography as a hobby. The professional photographer is gone. There are no commercial photographers, no architectural photographers, no catalog photographers (OK, a stretch, but still), no documentary photographers (What a tragic loss this is! No reason for this, at all!). Though there is no reason for the demand for these skill sets to have disappeared, it has nonetheless. Very poor photographs are being used in their stead, because they are seen as “good enough”. Of course, the wedding, school portrait and Bar Mitzah photographers have disappeared also, so not all is bad. One might claim there may be balance in the universe, after all, but the paparazzi are alive and well.

Except for the aforementioned scum of the Earth, the last man standing is me, the fine art photographer, and a snapshotting, iPhone wielding public that has no idea whatsoever, what that means!

The least affected by the digital photography revolution appears to be, me again, the fine art photographer. At least for the moment. It is harder though. Few hobbyists want to emulate us any more, simply because there are no hobbyists to speak of.

Though I will not miss having to explain to him over and over and over again, that NO, you cannot really do those things you read about in Popular Photography, I will miss the hobbyist and by extension, the magazines that fed him and his pursuits, that fed me.

For the last couple of years I have been a reluctant denizen of Facebook. I follow a couple dozen groups, mostly having to do with photography of course and have come to enjoy it, though I cannot claim to completely get Facebook. I still haven’t figured out what to do with my own Facebook page or how to keep people from posting things there that I don’t want them to post. Until I do, my contributions there will be less than inspirational. In fact, I pretty much don’t put anything on my own page, at all.

There are groups on Facebook for just about every aspect of photography, digital or analog, old processes and new. For someone wanting to learn just about any aspect of photography there is something to be had on Facebook. That is a good thing. And then again, it sometimes isn’t. The death of the photography magazine and the rise of the internet’s everyone is an expert nature leaves someone who is trying to learn equally open to advice from actual experts and the self-appointed variety. There is no filter any more and the result is the unfortunate state of affairs in which old and LARGE sources of misinformation seem doomed to be repeated in perpetuity.

In the late nineteenth century the Kallitype was invented and promptly fell flat on its face. Part of the problem was just poor timing, but much of the difficulty had to do with the constant repetition of false information. An incorrect formula would get published in one magazine, then be copied and republished, warts and all, by other magazines. New advocates would come up with their own formulas, most all of which were no improvement at all, publish those and, well, the end result is that a very substantial portion of what ended up in print about the Kallitype was quite substantially wrong.

Over time this sort of nonsense turned into an unofficial tradition in photography and to my dismay, that tradition has jumped right over the divide into the 21st century, in perfect health.

One of the groups on Facebook deals with new devotees of B&W film. Many are millennials who grew up with digital photography and have just discovered B&W film. From my perspective that is kind of humorous, but their devotion is in most cases, sincere. Sadly, they have also discovered a new generation of experts who are nothing of the kind.

From the second half of the 19th century right up through the first half of the 20th century, one of the most ridiculous but nonetheless fervently believed ideas held by amateur and professional photographers alike was the search for photography’s holy grail: the magic developer.

The pure tonnage of magazine pages and ink devoted to secret formulas and special additives that would miraculously turn a photographer’s negatives into Ansel Adams lookalikes and the resulting prints into masterpieces, was staggering. To my astonishment, the exact same thing is now happening all over again.

The current magic developer is one of several variations on pyro. Now, there is nothing wrong with pyro and its variations. It will get the job done, and well. But it is a staining developer and that is often more of a hindrance than a help. Especially if you are using variable contrast papers, because the color of the stain sends paper contrast off in unintended directions. But the big problem is not the pyro but how it is being used. And it is not just pyro. Other developers are being used in these manners also. Post after post talks about using pyro with techniques for reducing contrast where the subject matter does not call for reduced contrast: split developers/water bath / dilute still bath / minimal agitation, all classes of contraction development (reduced contrast) that I thoroughly shot down as both ineffectual and risky, a quarter century ago. And if you are disinclined to accept my expertise…

No problem! These techniques were also shot down by lots of people both before and after me. Even Ansel Adams pointed out that they were irrelevant with modern films.

These are development schemes intended to reduce contrast, as an approach to what in the Zone System is called contraction: intentional reduction of negative contrast for purposes of fitting an overscaled subject to a midrange grade of B&W silver-gelatin printing paper. These approaches were marginally effective with old thick emulsion films (there are no films like this any more, unless some of the Eastern European junk is still that far behind) but were highly prone to loss of film speed, uneven development and other forms of damage to the image. I debunked these methods in great detail during the early 1990’s and published several new techniques to replace them, techniques that did not suffer from the same serious drawbacks.

Now, someone, probably several someones, is advising people new to film photography to use these contrast reduction film development formulas/techniques for development of normal exposures and subject matter: precisely where they should NOT be used, even if they worked well!

The fact that there are differences in developers is not in question. There are high contrast developers and fine grain developers and low contrast developers and high acutance developers and all kinds of variations. But the differences in this day and age are really quite minor, especially in light of the quality of modern films.

Notwithstanding old communist block films still made with early twentieth century technology being flogged as modern marvels, modern B&W films have no need of specialized developers. They are already fine grain films. They already have high acutance. They can easily be developed to compensate for an overscaled subject with modern techniques that are far more controllable and dependable (talking about SLIMTs here) than any of the older methods that were designed to work with thick emulsion films that no longer exist. Well, that no longer exist unless you are buying cheap, junk film from Outer Slobovia.

One of the things modern B&W films do not do well is to compensate for underscaled subjects. That is, what in Zone System parlance is a subject that requires expansion (prolonged film development for higher contrast). Most modern films will surrender little more than N+1. But more than N+1 also does not require a magic developer. The problem is simply solved by using selenium toner as an intensifier, on top of the N+1 achieved with expanded development for a combined N+2; the most that is required for the vast majority of potential expansion subject matter. If even greater expansion is needed, it is best achieved by employing a higher contrast film with its contrast reduced to the needed level with a SLIMT. In other words use a high contrast film and think of the subject as needing contraction.

Why this rant? Because young photographers are being led astray. AGAIN!! Or, perhaps, STILL. They are chasing magic bullets just like they did for decades under the misguided tutelage of popular photography magazines. And there are still people out there, lots of people, who are more than happy to hold themselves out as experts, claiming to provide those magic bullets.

There are no magic bullets out there. No developer, no film, no secret incantations. Even the Zone System about which I have written so extensively and for which I have invented so many techniques and tools, is not a magic bullet.

Ansel Adams himself admitted in later years his regret that he had overhyped the Zone System such that many users viewed it too, as a magic bullet. The most that can be achieved with the Zone System is a negative that makes it easier to exert control in the printing process. The only magic in photography is that which takes place during printing and that is not magic, but hard-earned skill acquired over years of practice.

The real and ONLY secret in photography is in the making of the print and that brings us to the real point of this post.

The one thing you do not see in all those Facebook entries is any mention of the rigorous process of making the print. Instead, everyone is frantically searching for magic bullets while simply making straight positives of their film negatives with none of the work required to produce what is traditionally referred to as the fine print. And this is not isolated to silver-gelatin printing, either. It is also happening in what is generically referred to as alternative printing and even in the making of digital prints.

The only magic in photography is that of making the print and that is no magic at all. It is hard work involving a difficult to acquire skill set that few people today even know exists and even fewer pursue.

Strangely, the exact same skill set is required to make a print digitally as is needed in the traditional darkroom. The only differences are that with digital tools one gets to sit down, and there are more tools to accomplish the same things, in Photoshop.

Despite my status as (tongue in cheek) Zone System Guru, my advice to young film photographers today would be this: first and above all, learn to print. Use a single camera, a single lens, a single film, a single developer and develop all your film exactly the same way. Then, print, print, print, print, PRINT! After you have learned to print, in a decade or so, come see me and I will teach you the Zone System and the use of color filters. That, I believe, would be the proper order of things.

Over the past year or so I have reacquired some large format film equipment. But I don’t know why!

I am not at all disenchanted with digital tools, especially since I have been able to wrestle the inkjet print into submission on my terms and have pinned photogravure to the mat, at last.

Part of it had to do, at least this is what I told myself, with my experiments with 19th Century chemical print processes. I felt I needed to be able to make some negatives for some of those experiments.

Part of it too, was the siren call of all that dirt cheap large format equipment for sale on eBay that they couldn’t seem to even give away.

So I bought a couple of monorails, old Calumets, and a couple or three lenses and set up a small darkroom, for film processing only. That was very satisfying because I set it up to use equipment and processes I had invented myself. Open-ended tube processing in trays and my pride and joy, SLIMTs!! (Selective Latent Image Manipulation Techniques). This allowed me to feel less like the inventor of the buggy whip, since I would be using them again, even if no one else was. (They are actually still in use around the world, or so people tell me, from time to time.)

Then last spring an older couple was in the gallery and the conversation turned to equipment and process. When talking about photogravure I mentioned how hard it was to find decently priced large darkroom trays needed for preparing paper for photogravure. It turned out he had some and a bunch of other equipment that he ended up offering to give to me. Probably the fastest I ever said “yes” in my life!

So in addition to what I had already acquired, I became the happy recipient of 8×10, 5×7 and more (and better) 4×5 equipment, in addition to the trays and some other nice and timely tools. I am now better equipped with film cameras than I was way back when and I no longer have to stare wistfully at my Epson V700 scanner (the only smart purchase I made when starting the switch to digital), wondering why I have it. I have it to scan all the new negatives I am making for reasons still unknown to me.

But, I STILL don’t know exactly why I have this hardware or what I am going to do with it.

I have been using it. The 8×10 for some portraits of local colorful residents. The 4×5 and 5×7 for some images of the unusual buildings here in Bisbee, but nothing that I could unequivocally state is better done with film. Having camera movements again certainly makes the building photographs easier, but many of those problems can be resolved with a shift lens on the digital camera, and I seldom photograph buildings anyway.

So, I am adding film back into the mix without really knowing why. I can’t wait to find out!

An addendum: 8×10 B&W sheet film from Kodak is $8, per. Ilford film is half that. X-Ray film, depending on which variety you use is $1 per sheet or less, and works extremely well as a continuous tone film, if you use a SLIMT (see above). And if you dial back the latent image bleaching, it behaves quite similarly to what I used to call Zone System Expansion Film, Kodak’s Professional Copy Film Type 4125; a film I very much lamented losing.

It has been more than two years since I posted to this blog. Sometimes life throws an unexpected curve or two. The period of my absence has included the closing of my gallery in Alpine Texas, concomitant with a brief encounter with a woman/girlfriend wholly unfamiliar with any forms of truth, who managed to finagle a little bit of funds out of me, a move to Arizona partly for family reasons and a painfully extended search within Arizona for a suitable gallery/studio location.

I have finally (a year+ ago) settled into Bisbee, Arizona. Bisbee was a mining town, now turned tourist attraction with art galleries, some very good restaurants and lots of B&B’s.

Much of my time the last couple of years has been devoted to wringing the best out of the photogravure process, which I have finally been able to do. I have begun, just today, offering one-on-one workshops in this process. If interested, contact me privately.

Anyway, I’m back. This time I hope for an extended period. Of course like anyone, I need to hear feedback. If I hear nothing but crickets then I will assume no one is out there.

Million Dollar Motel Wallpaper

Within photographic circles, there has been a whirlwind on the internet over the last few days. It involves a recent claim of having set a record for “world’s most expensive photograph”.

Ignoring for the moment the many loudly clanging alarm bells set off by this claim, alarm bells that make one want to demand an immediate investigation, I prefer to address the fact that the mere making of such a claim, true or not, shines a spotlight on everything that is most despicable about the art world in its present incarnation and the egregious ignorance of the public with regard to art in general and fine art photography, in particular.

Where did this idea come from that art and artists are all about the big payoff? Why do people buy into this nonsense? This is not a variation of Lotto, with paint! Art is not a euphemism for worldwide casino. The idea of artists is not to see how much money you can make. It is a race to see how much good work you can produce, before you die! In fact, most artists are so disinterested in money that it makes it very difficult for them to afford the materials needed to create their art in the first place.

In my entire career, no conversation with another artist ever began with, “How much money did you make last month?” And I have never met an artist who reported having such an exchange, either. We care about money only to the extent that it allows us to continue to work.

These get rich concepts do not occur to artists and are not part of the real art world. They are part of the faux art world created by promoters and gallery owners. The one designed to relieve fools of their money, especially rich fools who have never read, The Emperor’s New Clothes.

Let me make sure I get this point across…

No real artist cares in the slightest about holding the record for most expensive, “anything at all”! It would never occur to an artist to issue a press release about something so meaningless. That sort of concept is foreign to an artist, senseless. It is no more rational than tweeting about the color clothing worn on that day. It is the art that matters, not the money! Money to an artist is simply a tool that makes it easier to produce more art. This doesn’t mean artists don’t think about money. They do. Mostly because they don’t have any. It means that money does not hold a position of importance in their lives, like it does for so many others. This does not arise from any feeling of superiority. It comes as the result of a highly-focused, single-purpose life where money is simply the vehicle that brings more materials and staves off eviction for another month.

The public, and a shamefully large percentage of the art world, apparently believe that artists are driven to produce new work out of a desire to one day strike it rich. No doubt they believe the lucky artists who do win the art world lotto will retire to a tropical island the next day. What a great seg-way into…

I’ve said this before, but it bears repeating. Most of the public believe that a fine art photograph is simply a technically superior, much larger, more gaudy, more saturated, better composed, but otherwise identical version of their own national park vacation pictures. They see absolutely nothing in a photograph that wasn’t in front of the camera at the time the photograph was snapped!

To most, there is no detectable difference between the two photographs shown below, save color and contour. The fault for this public defect must be laid at the feet of fine art photographers themselves. The public isn’t educated, because we didn’t bother to do it! And truth be known, many so-called fine art photographers don’t see a difference, either!

This is the one and only possible explanation for the fact the public so readily believes a ludicrous fairy tale told by a so-called fine art photographer marching down the street ahead of a brass band, proclaiming himself the greatest this, the biggest that, or the highest priced fill-in-the-blank (with the rude reference of your choice). Such a photographer is a perfect match for an ignorant public, because he too is incapable of seeing anything but the literal. He is the day-glo orange paint to their Elvis on black velvet.

An ignorant public is an easily fooled public, and there will always be charlatans who will claim that a dead fish floating in formaldehyde is art. Just as there will always be a wealthy person foolish enough to pay millions of dollars for it.

I would like to think there are no photographers on that same level, but I cannot find rose colored glasses that heavily tinted. I do hold out hope, and strongly suspect, there actually was no rich fool and that this is a case of complete fabrication. If the rich fool does exist, I sincerely hope that instead of paying cash, he traded a Kinkade painting. Then both parties will have received fair value.

dk

The Handmade Silver Print

This morning I was looking through a web site that contained images of photogravures, a strong interest and pursuit of mine, and read a comment about handmade prints having more value than inkjet images. This reminded me that the last several years, most of what I have seen regarding discussions of handmade prints has lumped silver-gelatin in with the far more laborious paths that include platinum/palladium, carbon, photogravure, etc., etc.

Silver-gelatin prints certainly do fall under the heading of handmade, I suppose. But I wonder if anyone has really thought about this at length and looked at it dispassionately, rather than out of fear for their personal ox being gored.

It is still in vogue among some, to speak in derogatory terms about digital prints. I began the very painful transition from analog to digital about seven years ago, not because I thought digital was necessarily better, but because I saw the handwriting on the wall and I wanted the additional tools that digital photography offered. Those tools have expanded a great deal in the interim.

In hindsight, I was right about that handwriting. Two (perhaps more now) of the Kodak films I relied upon, no longer exist. In particular, Kodak Professional Copy Film Type 4125, now gone, was a mainstay for me. I would take 30 film holders with me into the field, 10 of which were always loaded with Type 4125. It got used, a lot. One of the two variable contrast papers on which I most depended is also, no more. I would be hard pressed to work in silver-gelatin photography today, merely because of the lack of materials.

_________________________________________________________________

…and because it is probably needed for credibility in this post. I am a well-recognized expert on applied analog B&W photography, the inventor of a lot of techniques for analog B&W and color, have been published worldwide and am a former contributing editor to the recently defunct, Darkroom & Creative Camera Techniques magazine (last article of mine published was about 1997?). I have the knowledge and skill set with a wide margin to spare, and have analog B&W images in museums from here to Argentina. There are only a handful of people who I might find it difficult to out-do in the silver-gelatin darkroom. In short, I think I know what I’m talking about. Others may have a different opinion.

_________________________________________________________________

My premise(s) here is that there really is no added value to a silver-gelatin print based solely on the fact that it qualifies, technically, as a handmade photograph and that, based on those criteria which are held up to qualify a silver-gelatin print as handmade, inkjet prints are then also, handmade. That a collector would prefer silver over digital simply because silver is supposedly handmade is just absurd.

There is absolutely no virtue in something being merely handmade. We all have treasures we made in Kindergarten. They are truly handmade and none of them belong in galleries or museums (despite the ravings of morning-show hosts). A handmade object has no particular value as an object of art, unless skill and knowledge are also applied. There are many handmade silver prints out there that had no skill and very little knowledge involved in their production.

So, let’s first define the term handmade with reference to the fine art photograph, as including a high level of skill and knowledge.

Now we can go through the process…

First, we need to separate the high-level skill and knowledge from the donkey work. Loading a negative into a film carrier, raising or lowering the head of an enlarger on its column, focusing the image and starting an exposure, all require some skill and knowledge, but not anything a child can’t learn in a few minutes. Nothing really handmade about any of that. Anyone can do it.

Likewise, after the paper has been exposed, everything is pretty much drudgery. There is a certain amount of skill in running a piece of wet paper through successive trays without damaging it, but hardly anyone oohs and ahhhs over the fact you didn’t crease a piece of wet paper, even a very large piece of wet paper. And one must know how long to process, how to fix properly, tone, wash, flatten, spot, mount, cut a matte, etc. Spotting in particular requires a lot of skill, not easily acquired. (One mistake while spotting often means a ruined print.) But these are all after-the-fact things that no rational person would include under the heading of handmade, and are really just donkeywork. Backbreaking, intense, mind-numbing donkeywork, but donkeywork, nonetheless. When a painter completes a work, we do not include the coat of varnish he may put over it as a valuable addition to the handmade aspect of the painting.

The only meaningful handmade part of making a silver-gelatin print comes between the moment the enlarger exposure is begun, and the moment it ends. (The paper comes in a box, from a factory. Nothing handmade about that, either.) A lot of things can happen in that interim including dodging and burning, flashing, paper grade changes if using a variable contrast paper, and, well, um, er… not a lot more!

Now, I made that interim between turning the enlarger lamp on and off, sound very trivial. And it is, on paper (pun intended), about as trivial as many would like to make the digital printmaking process sound. But that supposedly trivial period during exposure takes many years to master. That mastery is decidedly not trivial. What happens between on and off is the real handmade aspect of the silver-gelatin photographic print and has been described by more than a few as being like a ballet. (Somehow, the thought of a fat old man in the darkroom doesn’t quite jibe with ballet for me, but you get the idea.)

What happens in the hands of a master, between the beginning and end of an exposure in the darkroom is truly inspiring, truly creative, truly handmade and truly art. But precisely the same ballet happens in front of a computer screen! The only meaningful difference is that one gets to sit in a chair and has more tools at his disposal.

In the darkroom, most of what happens during exposure is burning. Dodging can only be done for the length of the base exposure and not even that. If your base exposure is ten seconds, you can only dodge for eight or nine of them. Burning can be done for seconds, minutes… there is no limit. In fact, most fine prints are almost all burn and very little base exposure; sometimes, none at all.

There is zero difference between what happens during an exposure under an enlarger and what happens in Photoshop, save that what happens in Photoshop can be done more precisely, with more repeatability and with a greater array of tools. When an image has been created under the light of an enlarger, it is run through the automatic routine of the processing trays. When an image has been created in the glow of a computer screen, it is then run through the automatic processing tray of an inkjet printer. All that printer does is the drudgery of laying down ink where the photographer has told it to. All the processing tray does is develop the image already there.

During an analog exposure, one uses a simple piece of cardboard to add additional exposure to some areas of the image. In Photoshop a broader array of tools is used to do exactly the same thing, but more precisely and with more repeatability. In fact, in Photoshop, it doesn’t have to be repeated. It can be done only once. Oddly, very similar hand motions are used with the computer mouse to burn or dodge an image, as those used in the darkroom.

(I don’t recall any record of anyone ever claiming that a cave painting qualified as handmade, but an oil painting did not, because the oil painting was made with better tools that were more precise and easier to use.)

No less skill or knowledge are required to build an image in Photoshop than are needed in the darkroom. In fact, because of the greater array of tools, more skill and knowledge are probably required for Photoshop, if one intends to take full advantage of them. The nonsense repeated about Photoshop and requiring less skill is just that, nonsense. Digital photography does not take anything away from analog photography. But the reverse is also true.

The image, and the quality of that image, should be all that matters. That a photographer has fingernails blackened by selenium and a bad case of dermatitis brought on by repeated exposure to Metol, does not in any way make his images superior. The mindless automaton aspect that many would like to ascribe to those who today employ newer tools is just as ridiculous now, as it was every time it has been applied to others in the past 100+ years. There is absolutely nothing automatic or mechanical about a fine art photograph made digitally, and no special virtue that can be automatically ascribed to any photograph made by any means, old or new.

For anyone still tempted to speak in low terms about the digital print as opposed to a handmade silver-gelatin print; beware the folks making platinum/palladium, or gum, or carbon or photogravure or Colloidian or Daguerreotypes (Now, there’s some real handmade stuff for ya!) who might wish to make a case against YOUR ox!

It’s not whether you make an image by coating collodion onto a rock whilst whistling A Hard Day’s Night, that matters. Only the final image matters. If it looks like garbage, and an awful lot of handmade prints do, it matters not at all that it was handmade, except, perhaps, to a very, VERY foolish collector.

dk

Not Everything New Is A Good Thing

I wasn’t going to post today. Have a lot to do and little time. But a reader’s comment yesterday got both brain cells firing at once.

A year or two ago, someone, long since forgotten, told me that schools had stopped teaching cursive. For you older folks, that means longhand or script. (Don’t know why some people have to meddle and substitute a new word for what was a perfectly good existing word, except when there is an agenda behind doing so.) At first, I thought the person was joking. Not so. Apparently, children are now taught to print, but not to write, and barely that, the excuse being, now that we have computers, handwriting is no longer necessary.

That has got to be one of the silliest, and frankly, most stupid ideas I have heard in my life. It makes me question whether or not the folks who made such an absurd decision shouldn’t be relieved of their employment positions by being bodily thrown from the building. The practical uses notwithstanding (what if your battery dies?), handwriting is a form of expression, an art form if you will, and the second such form of expression (finger painting being the first) through which a child can connect with the world and share something of himself with others. It is unique to every single person on Earth and constitutes one of the first meaningful achievements in one’s life. It is part of becoming a civilized human being and essential to it.

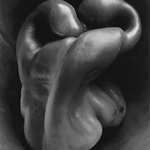

Only one gratuitous photograph today. This seems to be the appropriate place for it:

I’ve mentioned before that I am working on getting into photogravure, in a big way. The method for platemaking that I am using was developed (partly; the more I look into it, the more I find that a host of others have contributed) by Don Messec. He posted two short videos on the process, here and here, a few years ago. Those videos will give you the idea, but they are far from complete and Mr. Messec would like you to spend some money taking his workshop(s) to learn the whole process, which nonetheless has some problems he says he has yet to work out. Not having that money, I spent the last year or so experimenting, filling in the missing pieces and working out the aforementioned problems. Anyway, this long walk around the barn leads to the fact that I have, of course, been keeping notes. But not on my computer. That just seemed inappropriate. Clearly inappropriate. My notes on this new process are written in pencil, in a handmade, 8.5″x11″ leather notebook with light brown pages, hand-sewn to the leather. A long leather strip is used to close the book by wrapping it around the outside. (Purchased on eBay from a talented craftsperson. I just looked, she doesn’t seem to be there any more and there is now a LOT of poor imitation.) That is simply where such notes belong. Of course, if I had not been drilled at length in handwriting as a child, such a notebook would be simply a useless amalgam of leather and paper, because I would be incapable of writing in it, or at the very least, doing so would be such an arduous task as to make it wholly impractical. To handicap a child, let alone, generations of children, with the inability to write words on paper and the capacity to do it well, if not elegantly, is a crime, and absolutely, not progress.

Today I received an email. One of those solicitations from Amazon; you know, for books their software has deduced you might buy. Sometimes they are wildly nonsensical. Today, they thought I would buy two ebooks on the photographs of 19th century pictorialist photographers. EBOOKS! Why on Earth would I want a digital book of 100+ year old photographs? That makes no sense to me, at all. From a practical standpoint, in digital form, you have no idea what the images are going to look like compared to the actual photographs. And they are going to look different on just about every digital device. At least on paper, whatever the printer’s approximation of the original might be, that approximation will appear the same to everyone who buys the book. More importantly, there is a tactile, intimate experience with a book that is never going to happen with the digital format. A book of fine photographs belongs on paper, not on a screen. A digital instruction manual, on the other hand, makes perfect sense.

I recall an old Star Trek movie in which the crew landed on a planet where the indigenous people had rejected technology, even though their technology was far more advanced than that of the Star Trek crew. They lived a bucolic life, devoid of all the advanced tools they were more than capable of employing. That struck me as a very dumb premise. It makes no more sense to completely reject technology than it does to embrace it so absolutely as to reject all the finely honed skills and wonderful benefits of the past.

People can use and benefit from advanced technology without also rejecting all that has gone before. Many superior skills and ideas from the past are now lost forever, because new technology has replaced them and no one bothered to continue with the old. The so-called obsolete has a lot to teach us. (That includes people.)

Technology should be viewed as providing useful tools that are not always appropriate. Life is at its richest with a blend of both old and new. Progress is of little value when it leaves behind something that used to feed the soul.

I believe this is why there is currently somewhat of a resurgence in alternative photographic printing techniques. People are striving to reclaim some of that connection to a more complete experience that is often lost with new technology, digital photography in particular.

Though I have completely transitioned from analog to digital photography, that does not mean I am blind to its shortcomings. Digital camera resolution is decidedly inferior to analog, though analog printing rarely used all the resolution contained in film. Inkjet prints, especially those made on coated papers that are supposedly ideal for the purpose, are cold, sterile and far less permanent than their manufacturers would like us to believe; the reasons I print on watercolor papers.

Film and analog paper are disappearing at an incredible rate. Most of the B&W printing papers that existed just few years ago are gone. The many varieties of film have also largely vanished. Several of the techniques I invented for B&W photographers are now unusable because the films they relied upon no longer exist. Soon, analog B&W photographers will have a choice: switch to digital, or make their own B&W printing papers. This could be a good thing. Silver-based B&W papers at their best were frankly, not all that wonderful. Getting them to surrender a visualized image was often an uphill battle. Photographers might just end up producing something significantly superior, by hand.

Anyway, enough of my rant against blind, rampant consumerism and the adoration of technology. If the old is better, keep it. If you prefer analog photographic materials, stick to them. I’m 100% behind you. I have yet to experience anything in digital photography that can match the smell of a roll of 120 Tri-X on which the seal has just been cracked open.

dk