Black & White photography has always fascinated me. I was never interested in working with color, not even for casual photographs. B&W speaks to me. It allows me to see the world in a new way and to transform it into images I believe have something to say.

Practically everyone says they like B&W photographs. But most people don’t get black & white. Most photographers don’t get it. In fact, a lot of photographers who work in B&W don’t get it!

Black and white photography is really about the colors. And how those colors translate into gray tones. Arriving at the gray tones of a B&W photograph is not in any way straightforward or predetermined. It is very widely mutable. And it is, or should be, under the complete control of the photographer.

When photography first came into being, all photographic materials were of course B&W, and all were sensitive only to the blue portion of the visible spectrum. Skies were always washed out and very white in prints, plants and red things were usually very dark. It did not leave a lot of room for interpretation. Anything a photographer might want to alter about the gray tones in an image had to be done by controlling exposure to selected areas when making a print. This was effective, but only to a limited degree.

Orthochromatic films (sensitive to both blue and green) came along in 1873, giving photographers a way to finally control the gray tones in an image at the time of exposing the negative. A yellow or green filter could be placed over the lens and blue objects, such as the sky, would be darkened. This was often far more effective than trying to alter tones at the time of making a print.

Finally, panchromatic films sensitive to blue, green and red light, the full visible spectrum, came along in 1906. Photographers finally had a range of choices at the time of film exposure with regard to how gray tones would be represented in their photographs. By simply placing a colored filter in front of or behind the lens, virtually any color(s) in the scene could be made to come out darker or lighter in the final image. Some photographers carried only one or two filters, some none at all. Others, like myself, would utilize a dozen or more. But only one filter could be used per negative and the results were only moderately predictable. Surprises were very common and whatever guess a photographer made at the time of exposure was a guess he was permanently stuck with. In addition, one had to alter both exposure of the negative and its development, to compensate for the fact that filters changed more than just some of the gray tones.

From the very beginning, B&W photography was heavily dependent on the manipulation of the way colors affected the exposure of various portions of a negative.

More on this subject in an upcoming post.

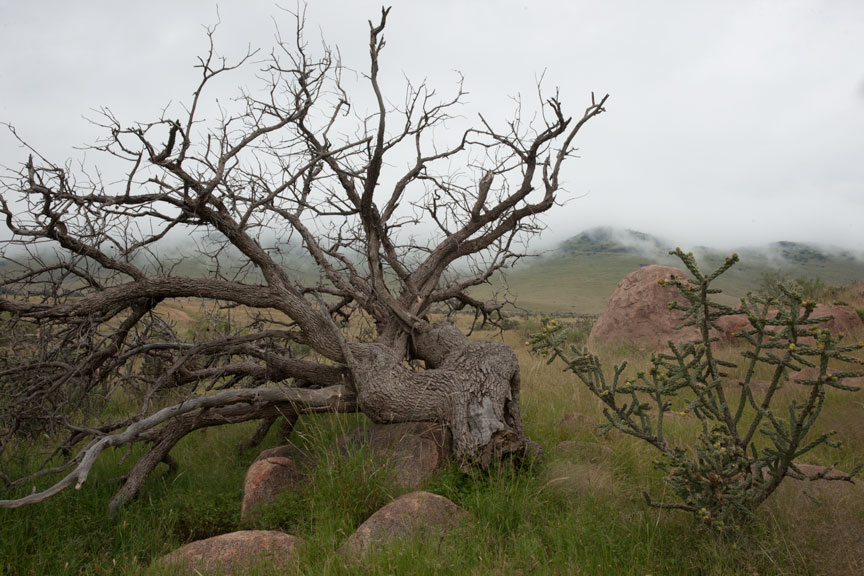

As for my day to day work. Yesterday I didn’t even remove the camera from the car. I went out, saw nothing. It was very bleak, rainy and hazy all day. This morning was quite similar, but I did use the camera a couple of times. This one looks potentially interesting:

dk