Just got back from an hour or so of working this evening. One thing looks promising. Also worked a couple of hours this morning, but that all looks like junk.

Of course, unless an image is unusable because it is technically flawed, such as being out of focus, or severely underexposed, I tend to hang on to them, just in case. Anything that looks good, even if badly damaged, I keep. More than once I have been going through images rejected years ago and found something good enough to make me puzzle why on Earth I rejected it in the first place.

I kept a whole project of 35mm street photography for 30+ years, knowing all the negatives were too severely damaged to be printable. Then Photoshop made them repairable and now I have a bunch a great images I never thought possible.

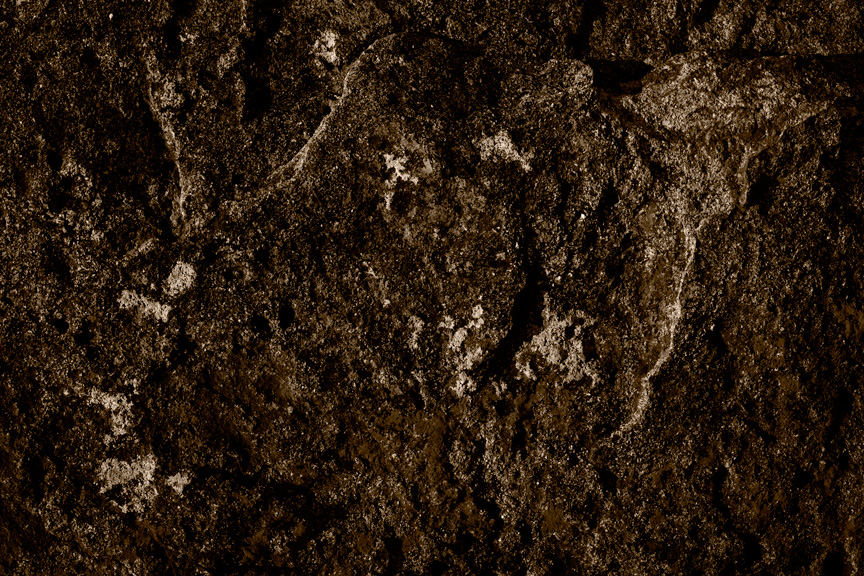

Here’s another of those images.

On the about page I mention that my work, as far as capture is concerned, is now all digital. I started making the changeover about seven years ago. It was not an easy transition. Digital capture is better in some ways and not so much in others. It’s like any other improvement in technology. You get some things and give up others.

Film had much higher resolution than digital capture has now, or is likely to have for another several years at least. If you compare a well-made print from medium or large format film to the digital counterpart, there is much more detail in the film image. However, I am speaking of nose pressed against glass comparison, which is of course, not the way to view fine art photographs. At reasonable viewing distances, it is difficult or impossible to tell there is a difference and digital images are adequate to the task, assuming a large sensor, tripod, careful procedure, etc. I would prefer higher resolution, but can live with what I am getting.

One very surprising defect, so to speak, with digital is that because the capture is in color and images are always purposely on the brink of overexposure (to get maximum information in the capture), there is not a lot of similarity between the RAW digital image on the screen and what I saw in my minds eye when I decided to take the photograph. Often I have to go back to an image a few times before I remember what I had in mind when I took it, or even apply manipulation to it in Photoshop to see if it jogs my memory. The unchanged digital capture usually looks pretty pathetic on the screen.

B&W film captures printed onto contact sheets were always much closer to what I intended because, well, they were B&W(!) and they were already partially manipulated tonally via use of colored filters for B&W, and they were exposed and developed for making the kind of print I had in mind. A quick look at a contact print made me instantly remember what I wanted when I shot the image. I miss that easy recognition.

Anyway, here’s some of the take from this morning. First, the captured image, heavily saturated but otherwise, untouched. Then a preliminary workup in B&W.

The grass swirl and rock abstract look moderately promising. The ranch house image is definitely headed for the scrap heap. The clouds are kind of interesting, but the rest of the image was pretty badly seen. Sometimes, in fact often, you find a great piece of an image, but nothing else to support it.

I am reminded of a quote from Alan Ross, one of Ansel Adams’ former assistants. “When I first went to work as Ansel’s assistant, one of the things that struck me the most was the realization, while going through boxes and boxes of his work, that he had made an awful lot of very ordinary photographs! I was somewhat stunned to learn that he had no illusions and no expectations that every film he exposed would wind up being another one of what he fondly called his Mona Lisas.”

Fine art photography is ten percent image capture, ten percent distinguishing a potentially great image and 80 percent being able to print that image masterfully. A lot of people think the lab makes the prints for fine art photographers. That is not remotely the case. Though a few fine art photographers do employ others to make their prints, the people employed are artists themselves and not available or even known, to the general public.

To paraphrase Ansel Adams’ musical metaphor, the captured image is simply a visual score. It is not art and a simple, literal translation of that captured image to paper is also not art. The performance of that score, the real art, is in making the print. No one goes to a concert to applaud the sheet music.

Here is a very preliminary work up of an image I captured this evening. This may have promise.

More tomorrow. (Leg feeling better, so I am more inclined to work.)