Not Everything New Is A Good Thing

I wasn’t going to post today. Have a lot to do and little time. But a reader’s comment yesterday got both brain cells firing at once.

A year or two ago, someone, long since forgotten, told me that schools had stopped teaching cursive. For you older folks, that means longhand or script. (Don’t know why some people have to meddle and substitute a new word for what was a perfectly good existing word, except when there is an agenda behind doing so.) At first, I thought the person was joking. Not so. Apparently, children are now taught to print, but not to write, and barely that, the excuse being, now that we have computers, handwriting is no longer necessary.

That has got to be one of the silliest, and frankly, most stupid ideas I have heard in my life. It makes me question whether or not the folks who made such an absurd decision shouldn’t be relieved of their employment positions by being bodily thrown from the building. The practical uses notwithstanding (what if your battery dies?), handwriting is a form of expression, an art form if you will, and the second such form of expression (finger painting being the first) through which a child can connect with the world and share something of himself with others. It is unique to every single person on Earth and constitutes one of the first meaningful achievements in one’s life. It is part of becoming a civilized human being and essential to it.

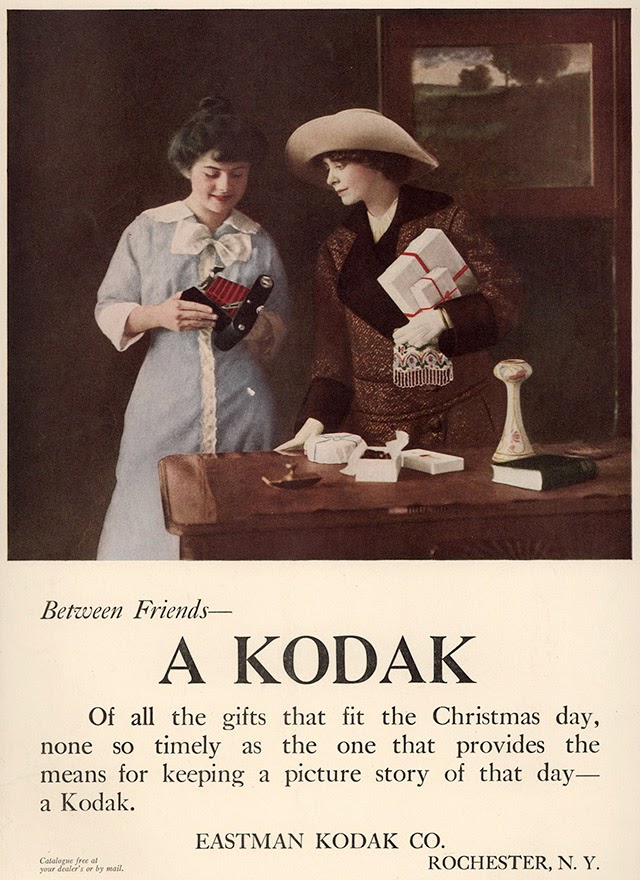

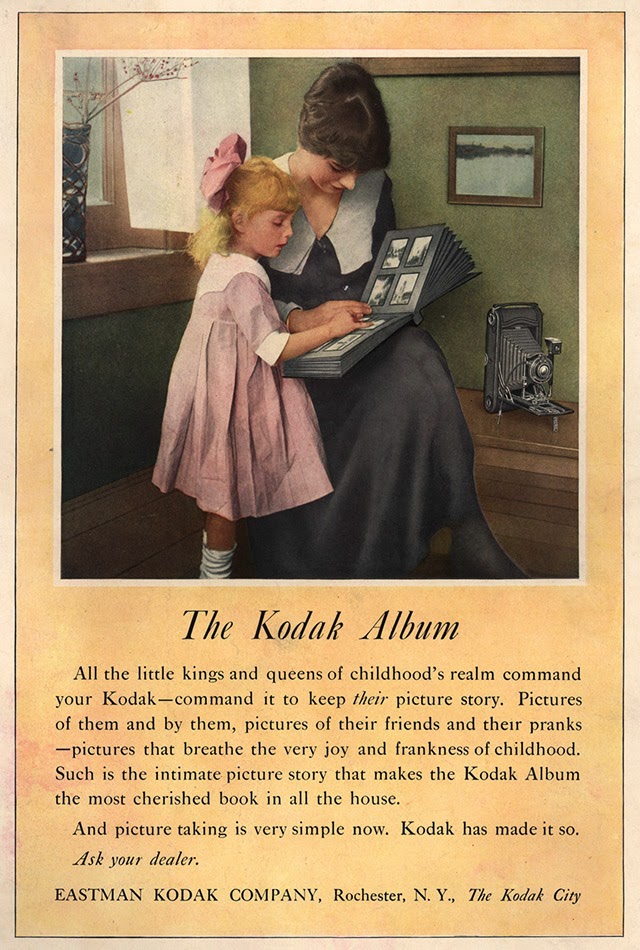

Only one gratuitous photograph today. This seems to be the appropriate place for it:

I’ve mentioned before that I am working on getting into photogravure, in a big way. The method for platemaking that I am using was developed (partly; the more I look into it, the more I find that a host of others have contributed) by Don Messec. He posted two short videos on the process, here and here, a few years ago. Those videos will give you the idea, but they are far from complete and Mr. Messec would like you to spend some money taking his workshop(s) to learn the whole process, which nonetheless has some problems he says he has yet to work out. Not having that money, I spent the last year or so experimenting, filling in the missing pieces and working out the aforementioned problems. Anyway, this long walk around the barn leads to the fact that I have, of course, been keeping notes. But not on my computer. That just seemed inappropriate. Clearly inappropriate. My notes on this new process are written in pencil, in a handmade, 8.5″x11″ leather notebook with light brown pages, hand-sewn to the leather. A long leather strip is used to close the book by wrapping it around the outside. (Purchased on eBay from a talented craftsperson. I just looked, she doesn’t seem to be there any more and there is now a LOT of poor imitation.) That is simply where such notes belong. Of course, if I had not been drilled at length in handwriting as a child, such a notebook would be simply a useless amalgam of leather and paper, because I would be incapable of writing in it, or at the very least, doing so would be such an arduous task as to make it wholly impractical. To handicap a child, let alone, generations of children, with the inability to write words on paper and the capacity to do it well, if not elegantly, is a crime, and absolutely, not progress.

Today I received an email. One of those solicitations from Amazon; you know, for books their software has deduced you might buy. Sometimes they are wildly nonsensical. Today, they thought I would buy two ebooks on the photographs of 19th century pictorialist photographers. EBOOKS! Why on Earth would I want a digital book of 100+ year old photographs? That makes no sense to me, at all. From a practical standpoint, in digital form, you have no idea what the images are going to look like compared to the actual photographs. And they are going to look different on just about every digital device. At least on paper, whatever the printer’s approximation of the original might be, that approximation will appear the same to everyone who buys the book. More importantly, there is a tactile, intimate experience with a book that is never going to happen with the digital format. A book of fine photographs belongs on paper, not on a screen. A digital instruction manual, on the other hand, makes perfect sense.

I recall an old Star Trek movie in which the crew landed on a planet where the indigenous people had rejected technology, even though their technology was far more advanced than that of the Star Trek crew. They lived a bucolic life, devoid of all the advanced tools they were more than capable of employing. That struck me as a very dumb premise. It makes no more sense to completely reject technology than it does to embrace it so absolutely as to reject all the finely honed skills and wonderful benefits of the past.

People can use and benefit from advanced technology without also rejecting all that has gone before. Many superior skills and ideas from the past are now lost forever, because new technology has replaced them and no one bothered to continue with the old. The so-called obsolete has a lot to teach us. (That includes people.)

Technology should be viewed as providing useful tools that are not always appropriate. Life is at its richest with a blend of both old and new. Progress is of little value when it leaves behind something that used to feed the soul.

I believe this is why there is currently somewhat of a resurgence in alternative photographic printing techniques. People are striving to reclaim some of that connection to a more complete experience that is often lost with new technology, digital photography in particular.

Though I have completely transitioned from analog to digital photography, that does not mean I am blind to its shortcomings. Digital camera resolution is decidedly inferior to analog, though analog printing rarely used all the resolution contained in film. Inkjet prints, especially those made on coated papers that are supposedly ideal for the purpose, are cold, sterile and far less permanent than their manufacturers would like us to believe; the reasons I print on watercolor papers.

Film and analog paper are disappearing at an incredible rate. Most of the B&W printing papers that existed just few years ago are gone. The many varieties of film have also largely vanished. Several of the techniques I invented for B&W photographers are now unusable because the films they relied upon no longer exist. Soon, analog B&W photographers will have a choice: switch to digital, or make their own B&W printing papers. This could be a good thing. Silver-based B&W papers at their best were frankly, not all that wonderful. Getting them to surrender a visualized image was often an uphill battle. Photographers might just end up producing something significantly superior, by hand.

Anyway, enough of my rant against blind, rampant consumerism and the adoration of technology. If the old is better, keep it. If you prefer analog photographic materials, stick to them. I’m 100% behind you. I have yet to experience anything in digital photography that can match the smell of a roll of 120 Tri-X on which the seal has just been cracked open.

dk